The recorder is the most highly developed member of the ancient family of internal duct flutes, flutes with a fixed windway formed by a wooden plug or block. Hitherto, it has been distinguished from other internal duct flutes by having holes for seven fingers and a single hole for the thumb of the upper hand.

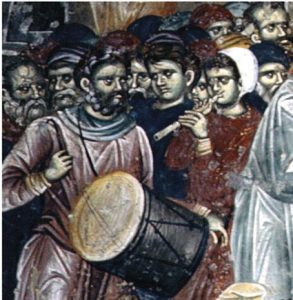

Perhaps the earliest illustration of a recorder as such is The Mocking of Jesus (after 1315), a fresco from the Church of St George, Staro Nagoričane, a village near Kumanova in (Yugoslav) Macedonia, painted by the court painters Michael Astrapas and Eutychios, in which a musician plays a cylindrical duct flute, the beak and window/labium of which are clearly visible, as are open holes beneath three lifted fingers of the player’s uppermost (left) hand and four holes for the fingers of the lowermost hand (also off the instrument).

The centre panel of La Virgen con el Niño [Altarpiece of Our Lady of the Angels], depicting a Virgin and Child surrounded by angels playing musical instruments (dated ca 1385, but possibly as late as 1400), painted by Pere (Pedro) Serra for the church of Santa Clara, Tortosa, now in the Museo Nacional d’Art de Catalunya Barcelona, shows what is clearly an alto-sized cylindrical recorder.

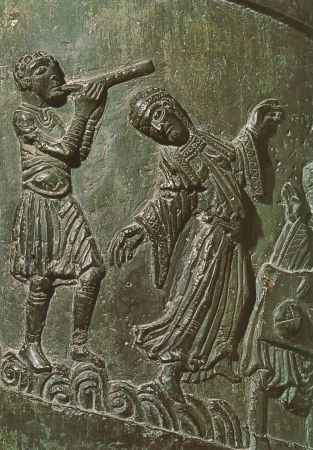

Before the 14th century, there are a number of illustrations of ambiguous ‘pipes’ which may (or may not) be duct flutes that may (or may not) be recorders. Amongst the earliest is one of the 28 spirally arranged scenes on the so-called Bernward Column (ca 1020), a bronze cast from Hildesheim Cathedral (Germany) which depicts Salome dancing to the accompaniment of a straight cylindrical pipe which has four holes visible, the lowest slightly offset. It is clasped between two hands, just above which there is a notch (?window); the mouthpiece is beak-shaped, and the player (a man) does not have the inflated cheeks characteristic of shawm players.

(c. 1020), Hildesheim Cathedral

And there are a number of other 11th-century examples, including a carving depicting King David and the Psalmists on an 11th-century stone pillar in the church at Bourbon-l’Achambault, St George, France which shows an ambiguous pipe that may be a duct flute (flageolet or recorder), accompanied by rebec and syrinx.

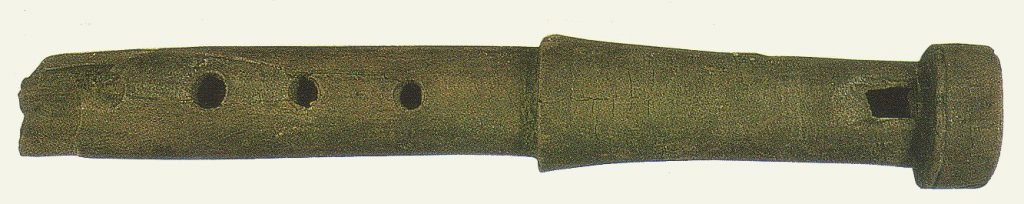

Amongst the oldest surviving more-or-less complete recorders, the so-called Dordrecht Recorder dates from the period 1335–1418. It was excavated from a well at the ruin of the Huis te Merwede (House on the Merwede) near Dordrecht, Holland.

This medieval recorder is most obviously characterised by its narrow, cylindrical bore (the internal tube passing down the middle of the instrument), which is largely responsible for the instrument’s tuning and response.

A second more-or-less complete medieval recorder dating from the 14th century has been reported from Göttingen (northern Germany) where it was found in a latrine in Weender Straßer 26 in 1987. This so-called Göttingen Recorder is part of the collection at the Stadtarchäologie Göttingen and has been described by Hakelberg (1995), Homo-Lechner (1996), Reiners (1997), and Doht (2006).

The Göttingen Recorder is made in one piece and has a thumb hole and holes for seven fingers, the lowest of which is doubled. It is 256 mm long and is also made of fruitwood, a species of Prunus. Its beak is damaged, which probably explains why it was discarded. There are narrowings of the bore between the first and second finger holes and between the second and third finger holes, as well as a very marked contraction close behind the seventh hole. The bore expands to 14.5 mm at the bottom of the instrument which has a distinctive bulbous foot.

Hakelberg (2002 & pers. comm. 2003) reports a third 14th-century recorder fragment found in the town of Esslingen, near Stuttgart (southern Germany), where it was excavated from the sediment of the mill channel of the Carmelite Monastery.

Interestingly, the Esslingen Recorder shows the very same characteristic turning profile as the Göttingen recorder. These fragments are preserved in the Landesdenkmalamt Baden-Württemberg, Stuttgart.

Utt (2006) reports that a fourth 14th-century recorder was found during an archaeological dig in August 2005 by Andres Tvauri in Tartu, Estonia (near the border with Russia). Like both the Göttingen and Esslingen instruments, the ‘Tartu Recorder’ was also found in a latrine in the backyard of 15 Üikooli Street. Other artifacts found with the Tartu Recorder allow it to be dated from the second half of the 14th century (Tvauri and Bernotas 2005, Tvauri and Utt 2007).

During the late medieval period, Tartu was an important Hanseatic city connecting Russia, especially Novgorod, with Western Europe. The body of the Tartu recorder is made from maple, the block from birch.

A fifth medieval recorder was found in a latrine in the old Hanseatic city Elblag (in former times Elbing) southeast of Danzig in Poland (Naumann 1999, Kirnbauer and Young 2001, Kirnbauer 2002).

The Elblag Recorder is intact and has been dated to the mid-15th century. Like the Dordrecht, Göttingen, and Tartu recorders, the Elblag recorder lacks the beak-shaped mouthpiece characteristic of the modern instrument. As with the other surviving late medieval recorders, the lowest interval of the Elblag recorder seems to have been a semitone. It was thus likely to have been pitched around d”, a tone higher than a modern soprano recorder.

A sixth medieval recorder was found after the Second World War in a latrine in the city of Nysa in Silesia, Poland, and dates from the 14th century (Mateusz Lacki, pers. comm. 2011). It is housed in the Muzeum w Nysie. The instrument is made from elder wood (Sambucus nigra). Although the block is missing, details of the window and labium are unmistakable. The blowing end of the instrument is truncate rather than beaked. It has single holes for seven fingers as well as the usual thumb hole. Again, the lowest interval of the Nysa recorder seems to have been a semitone.

A seventh medieval recorder (DK-Copenhagen: Musikhist. Mus. Inv. D9745), together with other objects, was found in 1919 during an excavation in central Copenhagen by archaeologists from the Danish National Museum. The instrument cannot by dated precisely, but was found amongst predominantly ‘late medieval objects’, which suggests a date in the second half of the 15th century. The recorder is well preserved, but extremely warped, and the block is missing. It is 283 mm long, made of boxwood, and has seven fingerholes on the front and a single thumbhole on the rear. The lowers fingerhole is doubled so that it can be played either right or left-handed. The outer profile is slightly waisted, narrowing from 20.5 mm at the top to c. 16.7 mm at fingerhole 4 from which it expands to 23.5 mm at the foot. The turning is far from smooth with a single ornamental groove at the end of the windway and the upper end of the window. A unique feature is a flat surface on the front of the instrument extending almost its full length from the block downwards. Rather than undercut, the somewhat oval fingerholes are slightly conical with the larger diameter at the outer surface. The windway is very short (22 mm) and there is no beak as such. Two holes on the side of the recorder in line with the middle of the block having a diameter of c. 4 mm suggest that the block was originally secured by a transverse peg or by means of a cord which might also have enabled the recorder to be suspended around the player’s neck. The window, labium and windway are crudely and irregularly fashioned. Part of the labium seems to have been broken off. The internal bore consists of two cylindrical sections: the upper 12.7 mm in diameter, the lower c. 10.3 mm (Bergstrøm 2020). Opening the lowest finger hole prouces a whole tone (Lasocki, in Lasocki & Ehrlich 2023: 2).

Clearly, we need a lot more information about those medieval recorders which have not been particularly well documented, to date. Most modern reconstructions are conjectural ones with the lowest note tuned to the tonic of their natural scale. Only a few reconstructions have been made with the lowermost interval a minor second (notably by Eugene Ilarianov and Tim Cranmore) but these involve complications of fingering that would have limited their performance. As Rowland-Jones (2014) suggests, it seems more likely that the archaeological examples are transitional instruments representing attempts to extend the range of the flageolet (six-holed pipe) by adding an additional hole for the little finger of the lowermost hand and another for the thumb of the uppermost hand. The seventh finger hole would have been closed only for the leading note in the lower octave, and the instruments were otherwise simply tuned and played as flageolets. The thumb hole could have been used to provide an easily playable middle tonic, and it would soon have found other uses.

For a more extended account of the medieval recorder see Lander (1996–2024).

References cited on this page

- Bergstrøm, Ture. 2020. “A Late Medieval Recorder from Copenhagen.” Galpin Society Journal 73: 220, 240, 244.

- Doht, Julia. 2006. “Die Göttinger Blockflöte [The Götingen Recorder].” Tibia 31 (2): 105–7.

- Hakelberg, Dietrich. 1995. “Some Recent Archaeo-Organological Finds in Germany.” Galpin Society Journal 48: 3–12.

- ———. 2002. “Was von einer ‘Klangschaft’ blieb? [What Remains of a Soundscape?].” Archäologie in Deutschland – Das Magazin 4: 31–32.

- Homo-Lechner, Catherine. 1996. Sons et instruments de musique au moyen age: archéologie musicale dans l’Europe du VIIe au XIVe siècles [Sounds and Musical Instruments of the Middle Ages: Musical Archaeology in Europe from the 7th to the 14th Century]. Collection des Hesperides. Paris: Editions Errance.

- Kirnbauer, Martin. 2002. “Musikzeugnisse des Mittelalter [Musical Finds from the Middle Ages].” Archäologie in Deutschland 6: 54–55.

- Kirnbauer, Martin, and Crawford Young. 2001. “Musikinstrumente aus einer mittelalterlichen Latrine.” Institutsbeilage der Schola Cantorum.

- Lander, Nicholas S. 1996–2024. “A Memento: The Medieval Recorder” Recorder Home Page.

- Lasocki, David R.G. 2023. “The Era of Medieval Recorders, 1300-1500.” In The Recorder, 1–47. Yale Musical Instrument Series. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300118704/the-recorder/.

- Naumann, Norbert. 1999. “Der Schatz aus der Latrine [Treasure from the latrine].” GEO Epoche 2: 116–23.

- Reiners, Hans. 1997. “Reflections on a Reconstruction of the 14th-Century Göttingen Recorder.” Galpin Society Journal 50: 31–42.

- Rowland-Jones, Anthony. 2014. “When Is a Recorder Not a Recorder?” FoMRHI Quarterly 127: 6–10.

- Tvauri, Andres, and Rivo Bernotas. 2005. “Archaeological Investigations Carried out by the University of Tartu in 2005.” AVE, 101–10.

- Tvauri, Andres, and Taavi-Mats Utt. 2007. “Medieval Recorder from Tartu, Estonia.” Estonian Journal of Archaeology / Eesti Arheoloogia Ajakiri 11 (1-2): 141–54.

- Utt, Taavi-Mats. 2006. “The Tartu Recorder.” ERTA Newsletter 23: 2.

Cite this article as: Lander, Nicholas S. 1996–2024. Recorder Home Page: History: Medieval period. Last accessed 28 April 2024. https://www.recorderhomepage.net/history/the-medieval-period/