The noun ‘recorder’

Outside England prior to the late 14th century there was no single word to differentiate the recorder from other kinds of internal duct-flute or from the equally popular transverse flute.

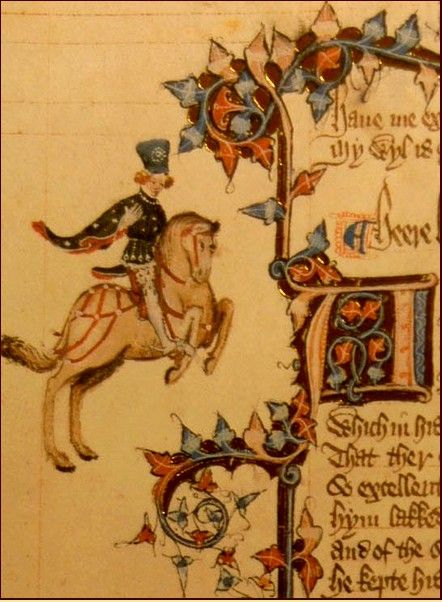

Although Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales (1340-1400) makes no direct reference to the recorder it is possible that, if he wasn’t whistling, Chaucer’s gay young Squire who was “Syngynge … or Floytynge, al the day” played a recorder, the ultimate expression of uselessness.

Chaucer’s Squire; from the Ellesmere manuscript of

The Canterbury Tales, Huntington Library, San Marino

In his House of Fame (1379-1380), Chaucer makes reference to woodwind musicians “that craftely begunne to pipe, both in doucet and in rede”. This has been taken to imply recorders and shawms respectively.

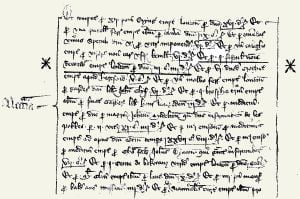

However, the earliest unequivocal reference to the recorder as such is provided by the household accounts of the Earl of Derby, Henry Bolingbroke (later King Henry IV) for 1388 which mentions:

“Et pro j fistula in nomine Recordour empta London pro domino iiij s iij d”

The superscript horizontal line and slash following the ‘o’ is an abbreviation for ‘ur’ in English court hand. Thus although the critical word looks like ‘Recordo’ it should really be rendered ‘Recordour’ and the entire entry should be translated

“And for one flute by name of Recorder bought in London for my lord, three shillings and four pence.”

Note that whereas the word ‘fistula’ (flute) is treated as a common noun, ‘Recordour’ is treated as if it were a proper noun like ‘London’, and that it is qualified by the word ‘nomine’. This would seem to indicate that both the word and the recorder itself were new to the language or unfamiliar.

It is possible that the recorder purchased on behalf of the Earl of Derby was for his own use. The future King Henry IV was a keen amateur musician (Trowell, 1957). Indeed, a piece in the early 15th-century Old Hall manuscript is ascribed ‘Roy Henry’, though the latter might refer to his more famous son who became Henry V. It is tempting to think of the Earl of Derby playing music with his wife: among the purchases ‘pro domina’ for the Countess of Derby are strings and pegs, presumably for her gittern (Rowland-Jones, 2001).

Galfridus Anglicus’ English/Latin dictionary, Promptorium Parvulorum (1440), gives “recorder or lytyll pype” as the translation of ‘canula’ citing an earlier dictionary the Campus Florum (c. 1335) as the authority. This latter is not the book by Thomas Wallensis of that same title in the library at Peterhouse, Cambridge, which consists of short tracts from the fathers and canonists, alphabetically arranged. But it could be a second work of the same name by the same author, an English-Latin vocabulary, known to have existed but now lost. In all likelihood, Thomas merely passed on earlier definitions of choraules [Gk χοραύλης], the leader of the chorus who played either canulae or fistulae], and the compiler of the Promptorium simply added the up-to-date equation with the recorder.

The recorder’s English literary debut (in the form ‘recorderys’) seems to have been John Lydgate’s Temple of Glas: Allas for thought (c. 1430), where it appears in the hands of a shepherd in a pastoral setting:

“… …

I myghte at leyser onys se,

And a-byde at lyberte,

Where as it doth so fayre sprede

A-geyn the su?me in euery mede,

On bankys hy a-mong the bromys,

Wher as these lytylle herdegromys

Floutyn ul the longe day,

Bothe in aprylle & in may,

"In here smale recorderys,

In floutys & in rede sperys,

Aboute this flour, til it be nyght;

It makyth hem so glad & lyght,

The grete beute to be-holde

Of this flour & sone onfolde

Hyre goodly fayre white levis,

Swettere than in 3ynge grevis

Is cheuyrfoyl or hawethorn,

Whan plente with hire fulle horn

Hyre sote baume cloth out-shede

On hony-souklys in the mede,

Fletywge ful of sugre newe;

... ..."

Before this time Lydgate made reference only to the ‘pipe’ and ‘floyte’ and their cognates, not to the recorder as such.

In Lydgate’s The Fall of Princes (1431-1438), the recorder appears again in a pastoral setting but this time in the hands of a supernatural being:

"Pan, god off Kynde, with his pipes seuene

Off recorderis fond first the melodies.

And Mercurie, that sit so hih in heuene,

First in his harpe fond sugred armonyes.

Holsum wynes thoruhfyned from ther lyes

Bachus fond first, of vynes heuy lade,

Licour off licours corages for to glade."

The Fall of Princes is a translation in 36,000 lines of a French version of Boccaccio’s De Casibus Virorum.

Many of the early poetic references to the recorder are to be found amongst those interminable lists of which the medieval mind was so fond. My favourite example is Richard de Holland’s Buke of the Howlat (? 1450):

"Thus our ladye they lofe, with liking and list,

Menstralis and musicians mo than I mene may,

The psaltery, the citholis, the soft cytharist,

The croude, and the monycordis, the gythornis gay,

The rote, and the recordour, the ribup, and rist,

The trump, and the taburn, the tympane but tray;

The dulsate, and the dulsacordis, the schalm of assay;

The amyable organis usit full oft,

Clarions loude knelis,

Portativis and bellis,

Cymbaclanis in the cellis

That soundis so soft."

As we have seen a ‘canula’ could be a recorder or a ‘lytyll pype’. Thus a recorder could be a pipe, also. This confusion (and more) is amply documented in literature. For instance, it is made as clear as mud in a wonderful punning passage in Anthony Copley‘s Wits Fittes and Fancies (1595) which pivots around this confusion and even brings in some botany, too:

“A merrie recorder of London mistaking the name of one Pepper, call’d him Piper: wherunto the partie excepting, and saying: Sir, you mistake, my name is Pepper, not Piper; hee answered: why, what difference is there (I pray thee) between Piper in Latin and Pepper in English; is it not all one? No, Sir, (reply’d the other) there is even as much difference betweene them, as is between a pipe and a recorder.”

Another and far more curious appellation for the recorder was that of ‘still pipe’ or ‘still flute’. The first use of the general term ‘still music’ seems to have been in the Privy Purse expenses of King Henry VII for the period 1485-1509 which notes payment to “styll mynstrells”, presumably purveyors of soft and fragile music.

On New Year’s Day, 1511, King Henry VIII (who played the recorder himself, in his youth) also employed “styll mynstrells” who were paid rather better than their louder brethren, the sackbut (or trombone) players. Needless to say, “the Queen’s mynstrells” fared worse than either!

from The King’s Psalter (16th century), British Library

In George Gascoigne’s Jocasta (1579) we find the stage direction:

“Before the second Acte, did sound a very doleful noise of flutes … In the order of the fifth and last dumb show, first the still pipes sounded a very mournful melodye, in which time there came upon the stage a woman clothed in a white garment …”

In John Marston’s Antonio’s Revenge (1600/1602) “still flutes sound softly” while Strotzo stages his repentance and dies with the question on his lips: “What strange portent is this?”

In The Two Noble Kinsmen (1613/1634) a joint effort of John Fletcher and William Shakespeare “still music of records” is indicated for a scene involving sacrifice and portent.

The term ‘still music’ is employed for the last time when recorders are called for to accompany Cupid in Thomas Heywood’s Love’s Mistress (1634).

The word ‘flute’, too, could imply recorder rather than the transverse flute, and indeed it usually did so until late in the 18th century.

During the Civil War (1642-1660) the theatres were closed and many stage musicians fled to the continent where they could make a living. On their return, the wind players amongst them came equipped with instruments that were the latest in French technology. The recorder was now made in three parts with a far more sophisticated bore giving it an extended range and a tonal character of far greater flexibility.

It was probably baroque recorders that so enchanted Samuel Pepys when he heard them played at the 1667 revival of Philip Massinger & Thomas Dekker’s The Virgin Martyr:

“Not that the play is worth much … But that which did please me beyond any thing in the whole world was the wind-musique when the angel comes down, which is so sweet that it ravished me, and indeed, in a word, did wrap up my soul so that it made me really sick, just as I have formerly been when in love with my wife; that neither then, nor all the evening going home, and at home, I was able to think of any thing, but remained all night transported, so as I could not believe that ever any musique hath that real command over the soul of a man as did this upon me; and makes me resolve to practice wind-musique, and to make my wife do the like.”

This new style of instrument brought with it yet another name, that of ‘flute douce’. In George Etherege’s The Man of Mode (1676) Sir Fopling Flutter asks:

“What, you are of the number of the ladies whose ears are grown so delicate since our operas, you can be charmed with nothing but flutes doux and French hautboys?”

There is a rather pointed counterpart to this passage in Thomas Shadwell’s A True Widow (1679):

“But how go matters in France? What new foppery is turned up trumps there?”

“Wit and women are quite out of fashion; so are flutes doux and fiddlers; drums and trumpets are their only music.”

Shadwell may simply be implying that the French are now only interested in war – women surely never go out of fashion! In fact, the decline of the recorder in France dates from about 1700 when La Barre astounded society with his flute-playing, followed later by Blavet.

The verb to record

The English verb ‘to record’ meaning ‘to get by heart, to commit to memory, to go over in one’s mind, or to repeat or say over as a lesson’, dates from as early as 1225 (OED2).

In Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde (ca 1374, iii. 2: 51) we read:

"Lay al this mene whyle Troilus, Recordinge his lessoun in this manere, `Ma fey!' thought he, `Thus wole I seye and thus; Thus wole I pleyne unto my lady dere; That word is good, and this shal be my chere; This nil I not foryeten in no wyse.' God leve him werken as he can devyse!"

And in the Golden Remains of the ever memorable Mr John Hales of Eaton College (1656) we read that:

“The Husband-man (faith St. Hierome) at the Plough-tail may sing an Hallelujah, the sweating Harvest-man may refresh himself with a Psalm, the Gardiner whilest he prunes his Vines and Arbors, may record some one of David’s Sonnets.”

It often seems to be overlooked that, whereas the instrument ‘the recorder’ seems to have acquired its name before or in 1388 (household accounts of the Earl of Derby), the old verb “to record” seems to have been applied to birds for the first time somewhat later.

In Barclay’s Mirror of Goodly Manners (c.1518, printed 1570) we read:

"Therfore first recorde thou, as birde within a cage,

… thy tunes tempring longe,

And then … forth with thy pleasaunt songe."

And in John Palsgrave’s L’esclarcissement de la langue francoyse (1530), a grammar of the French language for English readers, we find the following entries:

“I recorde as yonnge byrdes do: Je patelle.”

“This byrde recordeth all redy, she wyll synge within a whyle: C’est oyeslet patelle desja, elle chantera avant quil soyt longemps.”

“Recorder a pype fleute a. ix neufte trous.“

The term “fleute a neufte trous” indirectly furnishes the earliest corroboration of the meaning of ‘recorder’ in English.

After a gap of some 50 years we read in Thomas Watson’s England’s Helicon (c. 1580):

"Now birds record new harmonie,

And trees do whistle melodies;

Now everything that nature breeds,

Doth clad itself in pleasant weeds."

A tree might just as well “whistle melodies” by being turned into a recorder.

And in John Lyly’s Euphues and his England of the same year we find:

“Where vnder a sweete Arbour of Eglentine, be byrdes recording theyr sweete notes …”

In George Peele’s The Old Wive’s Tale (1595):

“The lark is mery and records her notes.”

Also in 1595, Valentine, one of Shakespeare’s Two Gentlemen of Verona, muses:

"Here can I sit alone, unseen of any,

And to the nightingale's complaining notes

Tune my distresses and record my woes."

And in Shakespeare’s Pericles (1608/9) we read:

"…… to the lute

She sung, and made the night-bird mute,

That still records with moan."

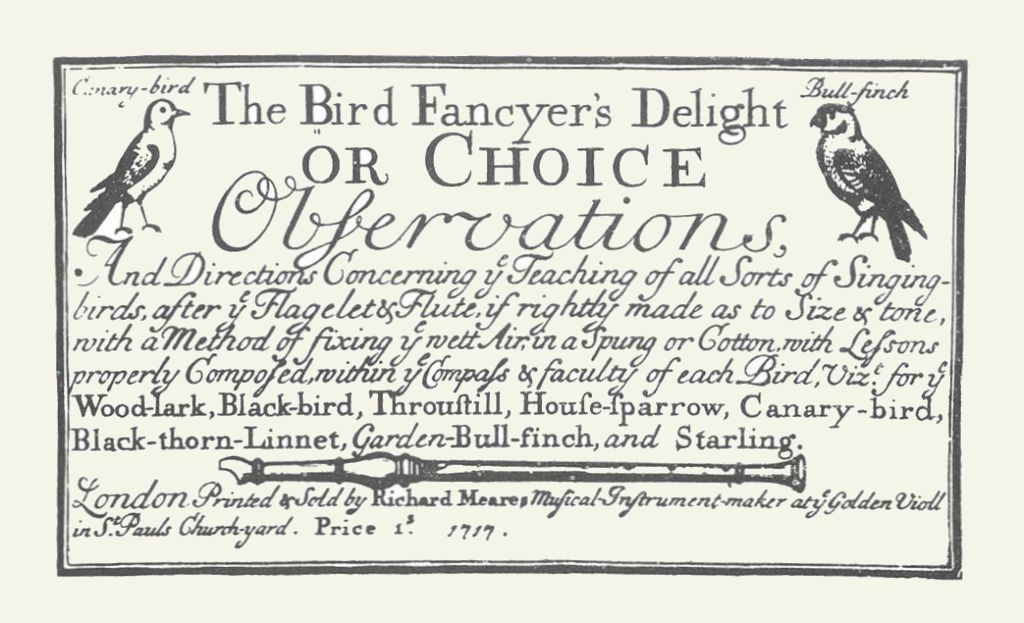

In this context, it is worth mentioning the delightfully silly English preoccupation with training caged birds to sing. The Bird Fancyer’s Delight Hills (1717) describes how this may be done with a variety of species including nightingale, bullfinch, blackbird, canary, woodlark, skylark, linnet, parrot, mynah bird, and house sparrow by placing them in a darkened cage and playing a suitable tune to them over and over again on a bird flageolet or a small recorder.

For more on teaching birds to sing with played examples from The Bird Fancyer’s Delight, see here.

Anthony Rowland-Jones (2014) has further suggested that the name ‘recorder’ was adopted for this instrument in reference to its use to assist singers who would otherwise find it difficult to hold their parts in tune and in time. The very portable recorder would have been a convenient aid for learning, rehearsing, and even performing such music. Eventually, with three instruments, a piece could be repeated (‘recorded’ ) to give the singers a rest and a change of sound for the listeners.

A more extended account of the etymology of the recorder and its occurrence in literature can be found in Lander (1996–2024a). A database of English literary and theatrical references to the recorder can be found in Lander (1996–2024b).

References cited on this page

- Hills, William. 1717. The Bird Fancyer’s Delight or Choice Observations and Directions Concerning the Teaching of All Sorts of Singing Birds after the Flagelet and Flute Rightly When Made as to Size and Tone with Lessons Properly Compos’d within the Compass and Faculty of Each Bird … London: Richard Meares; John Walsh.

- Lander, Nicholas S. 1996–2024a. “A Memento: The Medieval Recorder.” Recorder Home Page.

- Lander, Nicholas S. 1996–2024b. “Literary References.” Recorder Home Page.

- Rowland-Jones, Anthony. 2014. “When Is a Recorder Not a Recorder?” FoMRHI Quarterly 127: 6–10.

- Rowland-Jones, Anthony. 2001. “Some Thoughts on the Word ‘recorder’ and How It Was First Used in England.” Early Music Performer 8: 7–12.

- Trowell, Brian. 1957. “King Henry IV, Recorder-Player.” Galpin Society Journal 10: 83–84.

Cite this article as: Lander, Nicholas S. 1996–2024. Recorder Home Page: History: How the recorder got its name. Last accessed 25 April 2024. https://www.recorderhomepage.net/history/how-the-recorder-got-its-name/